For my assignment, I chose to visit the National Museum of Asian Art, and specifically went to their exhibit about Anyang (specifically called Anyang: China’s Ancient City of Kings). This exhibit was curated by J. Keith Wilson. The exhibit itself is made up of several parts. Various vessels that were used for honoring past ancestors, fermenting wine, pouring tea, and a variety of other cultural uses were on display, but we also see jade carvings and weapons, storage jars, and even wine containers. The vessels are intricately carved, showing various animals and mythological creatures on them. Oracle bones are on display; these were used in Shang-era China to divine the future and were in remarkably good condition (on some fragments, you can even see Chinese characters written on them in surprisingly high detail). The items themselves are laid out across two of the gallery rooms, in glass cases throughout both rooms.

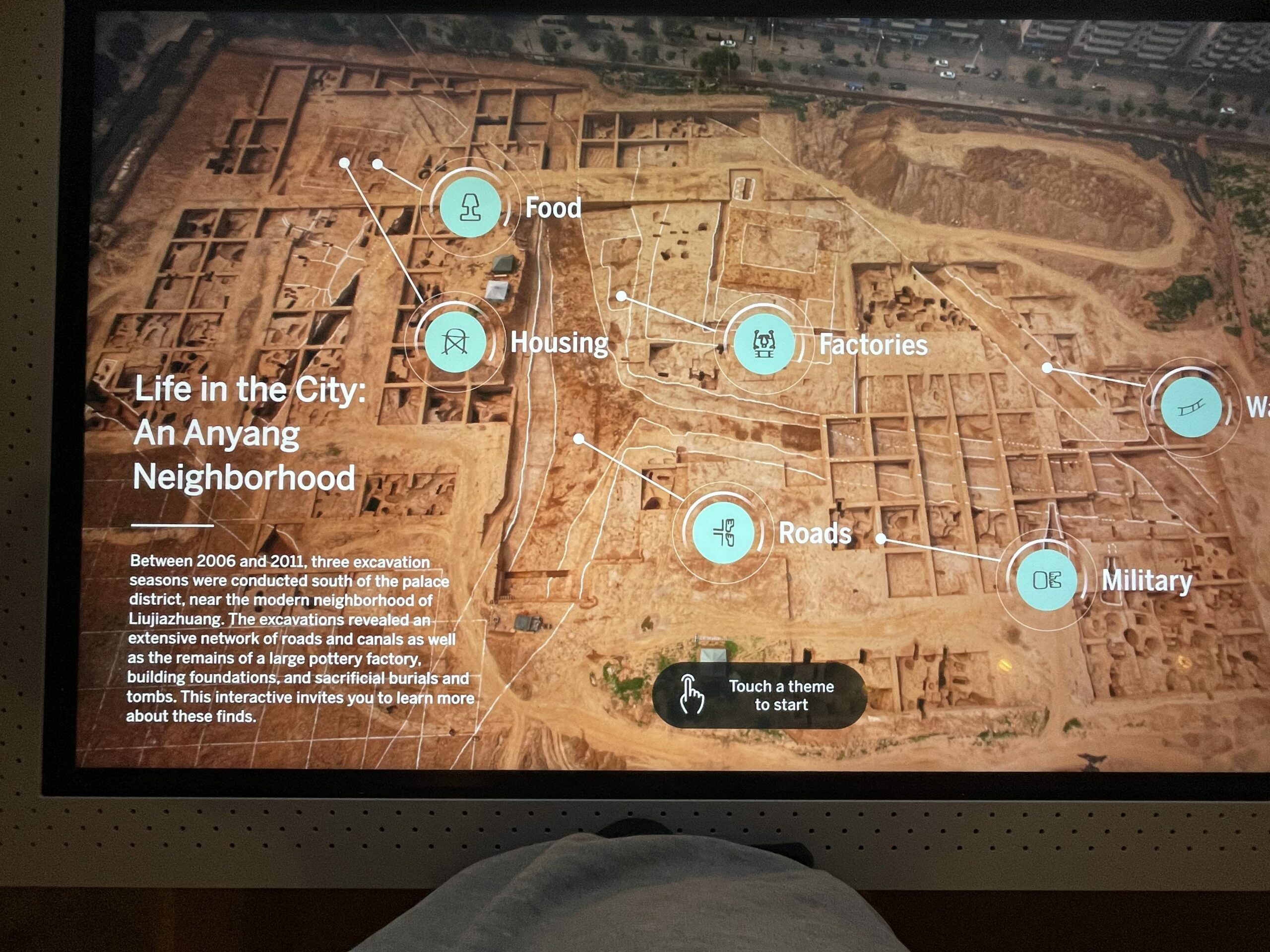

With regards to technology, the museum used three main points for the technology. The first was a map projected onto a small raised table that showed how the site at Anyang was discovered and excavated by Academia Sinica back in 1929 which was led by a member of the Freer Gallery staff named Li Chi (as a note, the Freer Gallery is now the National Museum of Asian Art). (Catlin) This shows various dig sites, what they found at the sites, etc. The second piece was an interactive, digital 3D model of oracle bones, where you could look at them in more detail and get a breakdown into how the divining process worked and what characters were written on them, what the characters meant, and further context as to why they were written. The third and final piece at the exhibit in person was the most detailed, and was actually an interactive map of the Anyang dig site. There were several nodes you could interact with to elaborate on, shown in the picture below.

Clicking on a node would go into greater detail about that area, how they know what was there, and how it impacted life in the city. For example, in the Roads theme, they go over construction of the roads, the main roads through Anyang, the bridges on these roads, etc. There’s a massive amount of detail that goes into each theme, and is presented in a way that’s really easy to understand while also being engaging. You can interact with it yourself at this link here. Going to the page online, you can find an AR activity for younger children that teaches them about Anyang, but this can be done at home (you don’t have to go to the National Museum of Asian Art to use it).

Regarding the main thesis/historical interpretation of the exhibit, I’d argue that the exhibit is really trying to give us a new glimpse into life in Shang China, and there are some discoveries that have created some conversation. For example, the exhibit’s curator talked about how from the writing on the oracle bones, it is possible that Anyang was a cradle of the written Chinese language, which he attributes in part to the fact that the bones were a far more durable and long-lasting material to write on. (Catlin) The exhibit really shows us life in a new context and shows us how different the world was back then, even for those living in China.

I think the main target audience is people interested in Antiquity China. This exhibit does really shine a new light onto life there and gives us a real idea of how important ritual was to the people of Anyang, while also humanizing them as we see how they lived life back then. While I do not think the exhibit is necessarily boring or anything, I do think that if you don’t have a good grasp on Ancient Chinese history (I took a class on it the previous semester, so most of it is still fresh in my head), I do think the exhibit may be a bit harder to get into.

It seems like the curator didn’t face any significant issues while developing the exhibit; on the contrary, it seems like, despite fraught U.S. and China relations, this project went rather well. This could be attributed to the fact that the Freer Gallery/National Museum of Asian Art have had a connection to this site since its original excavation, and as a result didn’t have any real logistical problems. The only thing I can think of being an issue is the political climate between China and the U.S. in recent years. For example, some analysts think the reason why China did not extend its loan of pandas to the National Zoo may be due to strained relations at the moment (Sands), and while I can’t find anything concrete about issues in the Anyang exhibit, I’m sure it’s something they had to keep in mind while designing and getting the exhibit ready.

Finally, I do think the exhibit did a great job at showing us the more physical parts of Shang society at Anyang, but I personally would’ve loved to have seen more context as to what was going on in Anyang and when it may have been affected by periods of upheaval or unrest, like a timeline of the city. Also, I would’ve liked to have seen some more decorations for the exhibit. The actual gallery itself was just in plain rooms, with no decoration on the walls besides the technology exhibits and plaques giving more info on Shang life in Anyang. Other than that, however, I found the exhibit to be extremely enjoyable, and would recommend it to anyone interested in Asian history in general.

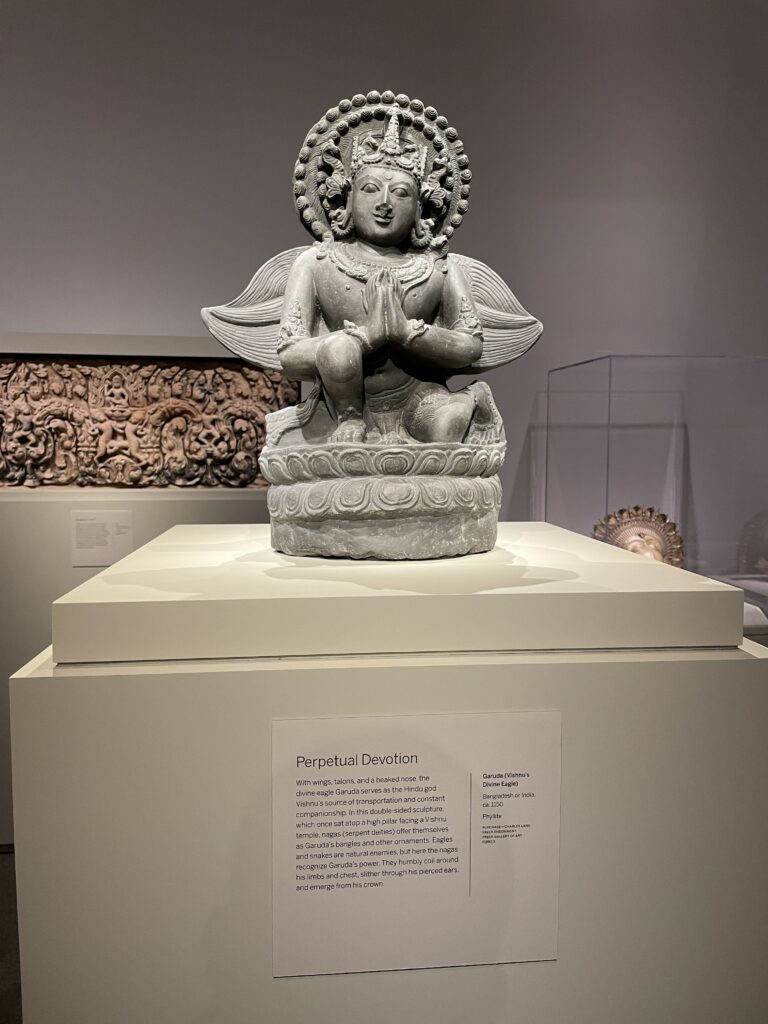

Attached are some other pictures from my visit (not of the Anyang exhibit, which I unfortunately neglected to get a picture of myself there, but hopefully the pictures here suffice).

Works Cited

Catlin, Roger. “A U.S.-China collaboration a century ago helped find riches of a lost civilization.” Smithsonian Magazine, 6 June 2023, www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/a-us-china-collaboration-a-century-ago-helped-find-riches-of-a-lost-civilization-180982272.

Sands, Leo. “China Takes Back Pandas From Zoos in U.S., U.K.” Washington Post, 28 Sept. 2023, www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/09/28/pandas-returning-china-dc-zoo.